Artist Interview | Jamal Thorne

Jamal Thorne is an artist living in Boston, MA. Working at the intersection of drawing and collage, Thorne explores the phenomenon of layering that occurs in digital spaces, translating into two-dimensional compositions how imagery from the past and present accumulate into a palimpsest that informs identity.

He has a BA from Morgan State University and an MFA from Northeastern University’s co-operative with The School of the Museum of Fine Arts. He is a recipient of the Joan Mitchell Foundation MFA Grant. Among other venues, he has exhibited his work at the Museum of Fine Art, Boston. He currently has a solo show up at Kingston Gallery, Fragments and Lost Verses, through July 26, 2020, and is also featured in the digital show Figuratively Speaking on Artsy through July 31, 2020.

Follow Jamal Thorne on Instagram @ajani_peace.

art_works: What motivated you to become an artist?

Jamal Thorne: Honestly, it was something I’ve always been good at and it’s always made me happy. Even at a young age, I recognized that something came alive in me when I “made” things. As I got older, my creative impulses turned into vandalism, but I still felt good when I did it. Being able to stand back and say to myself “I MADE that” always made life a little better.

a_w: What piece of yours is your favorite and why?

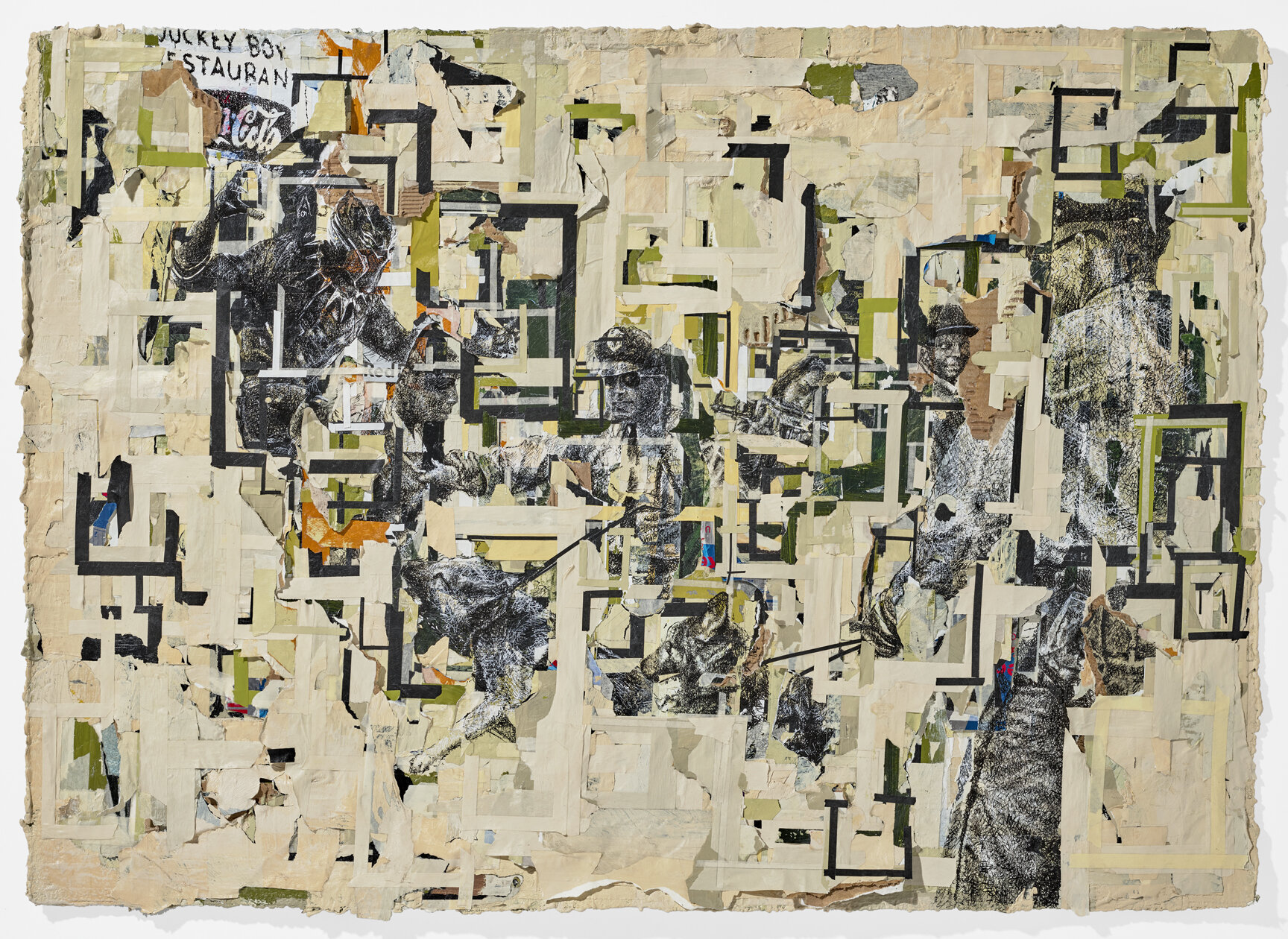

JT: Out of all the things I’ve made, Green No. 1 (2019) is easily my favorite. It was done in a period of real discord between me and a family member. There were days when I felt deep emotional pain, but the work needed to be finished for a show. Those emotions influenced the way I was responding to a photograph I was using for source material. There were also days of pride and anger, which also changed the way I felt about the images I was using. In the end, it’s the most accurate and genuine reflection of how I felt for a period of about 6 months.

a_w: What is your greatest achievement or something you are proud of?

JT: Finding my voice. Perhaps it’s more about discovering what my voice can actually do. Either way, when I started to see where the work was going and where my life was going, I felt strong. While I’ve always tried to present as a confident person, recognizing the strength in the things I do and make was a moment of personal pride.

a_w: What is the biggest challenge you face as an artist?

JT: Overcoming doubt is something I STILL struggle with even after finding my voice. There are moments where I look at what I’m doing and it all feels so trivial, implausible, or impossible. Pushing past those thoughts of doubt are a real struggle. Oddly enough, when I have doubts, I usually watch “Battle Rap” matches on the Ultimate Rap League YouTube channel. These individuals twist and morph language into something beautiful, aggressive, and unique. Watching them memorize entendre, wordplay, metaphors, and then perform their lyrical creations makes the impossible seem more reachable.

a_w: How has your work evolved over time?

JT: Mainly my work has shifted from an emphasis on technical skill to an emphasis on communication. For most of my life, I was only concerned with what looked “cool” on a surface level. It wasn’t until graduate school that I figured out the possibility of communication. When I grabbed onto that aspect, I decided I wanted to use my work to start conversations rather than stopping at communicating. When I think about the difference, conversations are more open-ended, they are less didactic, more inclusive, and there’s space for disagreement. It took me a while, but I’m far more interested in the discussion that comes from the work rather than the message that may come from the work.

a_w: What inspires your work?

JT: I don’t feel like there’s any singular point of inspiration. I think it all comes from life and experience. To a degree, I believe it’s my job to live and to process my experiences through my work. Visually, I look at Mark Bradford, Leonardo Drew, Cullen Washington, Seher Shah, Jackson Pollock. Most of these artists deal with the physicality of a surface, but they all look at identity and culture. In those regards, I feel kinship with them.

a_w: What messages do you try to send through your work?

JT: I don’t always think my work sends a message. If it does, I hope the message would come in the form of a question. “What do you see and why?” “Now that you’ve identified what you see and why you see it, what should we talk about?” If I really had to call out a message, it would be: “Slow down and find a moment for self-reflection.”

a_w: How have you been practicing art during the COVID-19 lockdown?

JT: I tried to bring my work home to develop a home practice, but it didn’t work. Having to work remotely from home required me to keep a certain kind of energy that is very different from what I bring to my studio practice. With both being in the same location, the two didn’t mix. I was always struggling to switch from teaching and administrative tasks to creative practice. When I moved my work back to my studio building, all while following strict COVID-19 related guidelines, I realized that I needed some separation between work and studio. The other thing I noticed is that the drive from one location to the next is incredibly important for getting into my creative focus and for coming away from it.

One thing I have noticed is that my approach to the work is more aggressive. When I start excavating the surface, it almost seems like I’m trying to claw my way out of a room. While we can go out a little more now, I still feel confined to some degree. Quarantine hasn’t really changed the imagery in the work yet, but I imagine something will be different in a few months or a year.

a_w: What role does art have in the context of social upheaval and protest?

JT: I try to think about artwork as a mirror. Art is made by people who channel their experiences, both emotional and physical, into their work. I think this is true from the three-year-old who picks up a crayon to the eighty-year-old who has been painting for most of his or her life. In any case, creators experience this moment of social upheaval, internalize it, and use their work to process it. The mirror aspect comes into play when creative individuals decide to show their work to the world in an effort to express how they understand the moment and how they’re processing this transformation. It’s our responsibility to use our creative modes of expression to enrich society’s emotional vocabulary. Even if one viewer takes a minute to engage with the work in a way that facilitates self-reflection or deeper understanding, the artwork is successful. Of course, this is just my opinion.

a_w: Do you think art can create social change and how does your practice operate within that?

JT: I don’t think art always has to generate social change, but I do believe that all art is socially engaged. Even if an artist makes something that is meant to be benign, I think that decision to disengage is meaningful. When a conversation arises and someone says, “I don’t have any comments on this topic,” that statement has meaning. I don’t necessarily think the decision deserves scrutiny but abstaining makes a statement about one’s relationship to any conversation, which includes conversations about social change. If art facilitates social change, that’s great...but I don’t think it’s required.

I firmly believe there needs to be a revolution when it comes to self-perception and the way we perceive other people. It’s the reason why I try to use my work as a catalyst for self-reflection. If we can look at ourselves as constantly evolving entities who can learn more about our own identity and other people, perhaps that self-reflective space becomes the reason for being open to difficult conversations around race, wealth, gender, identity, and all of the things that are used to divide us from one another. Perhaps that self-reflective space causes a viewer to say, “If I’m still learning about myself, there’s still room for me to learn about other people.” To do these things requires a level of vulnerability that I try to put on full display with my work.

I absolutely believe I have a responsibility to use my creativity to address the issues that provoke a response within me. If I’m talented enough to get someone to pay attention, I believe it’s my responsibility to use the opportunity to start a conversation.